Anthropologists Prefer to Use the Term Verbal Arts Rather Than the Term Folklore Because the Term

Folklore is the body of culture shared by a item grouping of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or grouping. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends,[1] proverbs and jokes. They include material civilisation, ranging from traditional building styles to handmade toys common to the grouping. Folklore also includes customary lore, taking deportment for folk beliefs, the forms and rituals of celebrations such as Christmas and weddings, folk dances and initiation rites. Each i of these, either singly or in combination, is considered a folklore artifact. Simply every bit essential as the form, folklore also encompasses the manual of these artifacts from one region to another or from one generation to the next. Folklore is not something one tin typically gain in a formal school curriculum or study in the fine arts. Instead, these traditions are passed along informally from ane individual to another either through verbal instruction or demonstration. The academic report of folklore is called folklore studies or folkloristics, and information technology can be explored at undergraduate, graduate and Ph.D. levels.[2]

Overview [edit]

Indian Folk Worship at Batu Caves, Selangor Malaysia

Serbian Folk Group, Music and Costume. A group of performers sharing traditional Serbian folk music on the streets of Belgrade, Serbia.

The word folklore, a compound of folk and lore, was coined in 1846 past the Englishman William Thoms,[three] who contrived the term as a replacement for the contemporary terminology of "popular antiquities" or "popular literature". The second half of the discussion, lore, comes from Old English lār 'instruction'. It is the cognition and traditions of a item group, frequently passed along by give-and-take of mouth.[4]

The concept of folk has varied over fourth dimension. When Thoms kickoff created this term, folk applied only to rural, frequently poor and illiterate peasants. A more modern definition of folk is a social group that includes two or more persons with common traits, who express their shared identity through distinctive traditions. "Folk is a flexible concept which can refer to a nation every bit in American folklore or to a single family unit."[v] This expanded social definition of folk supports a broader view of the textile, i.e. the lore, considered to be sociology artifacts. These at present include all "things people make with words (verbal lore), things they make with their easily (material lore), and things they make with their actions (customary lore)".[vi] Folklore is no longer considered to be limited to that which is sometime or obsolete. These folk artifacts go along to be passed along informally, as a rule anonymously, and always in multiple variants. The folk group is not individualistic, information technology is community-based and nurtures its lore in community. "Every bit new groups sally, new folklore is created… surfers, motorcyclists, computer programmers".[7] In direct contrast to high culture, where any single work of a named artist is protected by copyright law, folklore is a part of shared identity inside a common social group.[8]

Having identified folk artifacts, the professional folklorist strives to understand the significance of these behavior, customs, and objects for the grouping, since these cultural units[nine] would not be passed along unless they had some continued relevance within the group. That pregnant tin nonetheless shift and morph, for example: the Halloween celebration of the 21st century is not the All Hallows' Eve of the Middle Ages, and even gives rise to its ain prepare of urban legends independent of the historical commemoration; the cleansing rituals of Orthodox Judaism were originally good public health in a land with trivial water, but now these community signify for some people identification as an Orthodox Jew. By comparison, a mutual action such every bit tooth brushing, which is also transmitted within a group, remains a practical hygiene and health event and does non rise to the level of a group-defining tradition.[ten] Tradition is initially remembered behavior; once information technology loses its practical purpose, at that place is no reason for further manual unless it has been imbued with meaning beyond the initial practicality of the action. This significant is at the core of folkloristics, the report of sociology.[11]

With an increasingly theoretical sophistication of the social sciences, it has become evident that folklore is a naturally occurring and necessary component of any social group; information technology is indeed all effectually us.[12] Sociology does not have to be old or antiquated, it continues to be created and transmitted, and in any group it is used to differentiate between "us" and "them".

Origin and development of folklore studies [edit]

Folklore began to distinguish itself equally an autonomous discipline during the period of romantic nationalism in Europe. A particular figure in this evolution was Johann Gottfried von Herder, whose writings in the 1770s presented oral traditions as organic processes grounded in locale. Afterwards the German states were invaded by Napoleonic France, Herder'south approach was adopted past many of his young man Germans who systematized the recorded folk traditions and used them in their process of nation building. This procedure was enthusiastically embraced by smaller nations like Finland, Estonia, and Hungary, which were seeking political independence from their dominant neighbours.[xiii]

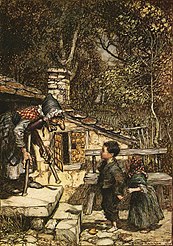

Folklore equally a field of study further developed among 19th century European scholars who were contrasting tradition with the newly developing modernity. Its focus was the oral folklore of the rural peasant populations, which were considered as remainder and survivals of the past that continued to exist within the lower strata of society.[14] The "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" of the Brothers Grimm (first published 1812) is the best known just by no ways only collection of verbal sociology of the European peasantry of that time. This interest in stories, sayings and songs continued throughout the 19th century and aligned the fledgling discipline of folkloristics with literature and mythology. By the turn into the 20th century the number and sophistication of folklore studies and folklorists had grown both in Europe and North America. Whereas European folklorists remained focused on the oral folklore of the homogenous peasant populations in their regions, the American folklorists, led by Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict, chose to consider Native American cultures in their research, and included the totality of their community and behavior as sociology. This stardom aligned American folkloristics with cultural anthropology and ethnology, using the aforementioned techniques of data drove in their field inquiry. This divided alliance of folkloristics between the humanities in Europe and the social sciences in America offers a wealth of theoretical vantage points and inquiry tools to the field of folkloristics as a whole, even as it continues to be a point of discussion within the field itself.[15]

The term folkloristics, along with the alternative name folklore studies,[note i] became widely used in the 1950s to distinguish the academic study of traditional culture from the folklore artifacts themselves. When the American Folklife Preservation Human action (Public Law 94-201) was passed by the U.S. Congress in January 1976,[16] to coincide with the Bicentennial Celebration, folkloristics in the United States came of age.

"…[Folklife] ways the traditional expressive culture shared within the diverse groups in the Us: familial, indigenous, occupational, religious, regional; expressive culture includes a broad range of creative and symbolic forms such equally custom, belief, technical skill, linguistic communication, literature, fine art, compages, music, play, trip the light fantastic toe, drama, ritual, pageantry, handicraft; these expressions are mainly learned orally, past imitation, or in performance, and are generally maintained without benefit of formal instruction or institutional direction."

Added to the extensive array of other legislation designed to protect the natural and cultural heritage of the U.s., this law also marks a shift in national awareness. It gives vocalism to a growing agreement that cultural diversity is a national forcefulness and a resource worthy of protection. Paradoxically, it is a unifying feature, non something that separates the citizens of a country. "We no longer view cultural divergence equally a trouble to be solved, but as a tremendous opportunity. In the diversity of American folklife we find a market place teeming with the exchange of traditional forms and cultural ideas, a rich resource for Americans".[17] This diversity is historic annually at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and many other folklife fests around the state.

There are numerous other definitions. According to William Bascom major commodity on the topic there are "four functions to folklore":[eighteen]

- Sociology lets people escape from repressions imposed upon them by order.

- Sociology validates civilization, justifying its rituals and institutions to those who perform and observe them.

- Sociology is a pedagogic device which reinforces morals and values and builds wit.

- Sociology is a ways of applying social force per unit area and exercising social control.

Definition of "folk" [edit]

Sociology theater in Mansoura, Egypt

The folk of the 19th century, the social group identified in the original term "folklore", was characterized past being rural, illiterate and poor. They were the peasants living in the countryside, in dissimilarity to the urban populace of the cities. Only toward the finish of the century did the urban proletariat (on the coattails of Marxist theory) go included with the rural poor equally folk. The common feature in this expanded definition of folk was their identification as the underclass of society.[19]

Moving forrard into the 20th century, in tandem with new thinking in the social sciences, folklorists also revised and expanded their concept of the folk group. By the 1960s it was understood that social groups, i.e. folk groups, were all around us; each individual is enmeshed in a multitude of differing identities and their concomitant social groups. The first grouping that each of usa is born into is the family unit, and each family has its own unique family folklore. As a child grows into an private, its identities also increase to include age, language, ethnicity, occupation, etc. Each of these cohorts has its own folklore, and every bit one folklorist points out, this is "non idle speculation… Decades of fieldwork have demonstrated conclusively that these groups do have their own folklore."[7] In this modern agreement, sociology is a office of shared identity within whatsoever social group.[eight]

This folklore can include jokes, sayings and expected beliefs in multiple variants, always transmitted in an breezy manner. For the most part it will be learned by observation, imitation, repetition or correction by other group members. This informal cognition is used to confirm and re-inforce the identity of the group. It can be used both internally within the grouping to express their mutual identity, for example in an initiation ceremony for new members. Or it tin exist used externally to differentiate the grouping from outsiders, like a folkdance sit-in at a community festival. Significant to folklorists here is that there are two opposing just equally valid ways to use this in the written report of a group: you can start with an identified group in order to explore its folklore, or you can identify folklore items and utilise them to identify the social group.[twenty]

Beginning in the 1960s, a farther expansion of the concept of folk began to unfold through the study of folklore. Individual researchers identified folk groups that had previously been overlooked and ignored. One notable case of this is found in an issue of the Journal of American Folklore, published in 1975, which is dedicated exclusively to articles on women'due south folklore, with approaches that had not come from a man's perspective.[note two] Other groups that were highlighted every bit part of this broadened agreement of the folk group were non-traditional families, occupational groups, and families that pursued the production of folk items over multiple generations.

Folklore genres [edit]

United Arab Emirates traditional folk trip the light fantastic toe, the women flip their hair sideways in brightly coloured traditional dress.

Individual folklore artifacts are commonly classified every bit 1 of three types: material, verbal or customary lore. For the most part self-explanatory, these categories include physical objects (cloth folklore), common sayings, expressions, stories and songs (verbal folklore), and behavior and ways of doing things (customary sociology). There is also a quaternary major subgenre defined for children's folklore and games (childlore), as the collection and interpretation of this fertile topic is particular to schoolhouse yards and neighborhood streets.[21] Each of these genres and their subtypes is intended to organize and categorize the folklore artifacts; they provide common vocabulary and consistent labeling for folklorists to communicate with each other.

That said, each artifact is unique; in fact ane of the characteristics of all sociology artifacts is their variation within genres and types.[22] This is in direct dissimilarity to manufactured appurtenances, where the goal in production is to create identical products and any variations are considered mistakes. It is however merely this required variation that makes identification and classification of the defining features a claiming. And while this classification is essential for the bailiwick area of folkloristics, it remains merely labeling, and adds trivial to an understanding of the traditional development and meaning of the artifacts themselves.[23]

Necessary every bit they are, genre classifications are misleading in their oversimplification of the subject area area. Folklore artifacts are never cocky-contained, they do not stand up in isolation but are particulars in the self-representation of a community. Different genres are often combined with each other to mark an event.[24] So a birthday commemoration might include a song or formulaic way of greeting the birthday child (verbal), presentation of a cake and wrapped presents (material), likewise every bit customs to honor the private, such as sitting at the head of the table, and blowing out the candles with a wish. There might also exist special games played at birthday parties which are not by and large played at other times. Calculation to the complexity of the interpretation, the birthday political party for a seven-twelvemonth-quondam will non be identical to the altogether party for that aforementioned child as a six-year-old, even though they follow the aforementioned model. For each artifact embodies a single variant of a operation in a given time and space. The task of the folklorist becomes to identify inside this surfeit of variables the constants and the expressed meaning that shimmer through all variations: honoring of the individual within the circumvolve of family and friends, gifting to express their value and worth to the grouping, and of course, the festival food and drink every bit signifiers of the event.

Verbal tradition [edit]

The formal definition of verbal lore is words, both written and oral, that are "spoken, sung, voiced forms of traditional utterance that show repetitive patterns."[25] Crucial here are the repetitive patterns. Exact lore is non but any conversation, only words and phrases conforming to a traditional configuration recognized by both the speaker and the audience. For narrative types past definition have consistent construction, and follow an existing model in their narrative form.[note 3] As simply one unproblematic example, in English the phrase "An elephant walks into a bar…" instantaneously flags the following text every bit a joke. It might be i yous've already heard, but it might be 1 that the speaker has merely idea upwardly inside the current context. Another instance is the child's song Onetime MacDonald Had a Subcontract, where each operation is distinctive in the animals named, their club and their sounds. Songs such every bit this are used to express cultural values (farms are of import, farmers are old and weather-beaten) and teach children about different domesticated animals.[26]

Verbal sociology was the original sociology, the artifacts defined by William Thoms as older, oral cultural traditions of the rural populace. In his 1846 published call for assistance in documenting antiquities, Thoms was echoing scholars from across the European continent to collect artifacts of exact lore. By the beginning of the 20th century these collections had grown to include artifacts from around the earth and across several centuries. A organisation to organize and categorize them became necessary.[27] Antti Aarne published a outset classification organization for folktales in 1910. This was afterward expanded into the Aarne–Thompson classification system by Stith Thompson and remains the standard classification organization for European folktales and other types of oral literature. As the number of classified oral artifacts grew, similarities were noted in items that had been collected from very unlike geographic regions, ethnic groups and epochs, giving rise to the Historic–Geographic Method, a methodology that dominated folkloristics in the first half of the 20th century.

When William Thoms outset published his appeal to document the exact lore of the rural populations, it was believed these folk artifacts would die out as the population became literate. Over the past two centuries this belief has proven to be wrong; folklorists keep to collect verbal lore in both written and spoken form from all social groups. Some variants might have been captured in published collections, simply much of it is nevertheless transmitted orally and indeed continues to be generated in new forms and variants at an alarming charge per unit.

Below is listed a small-scale sampling of types and examples of verbal lore.

- Aloha

- Ballads

- Blessings

- Bluegrass

- Chants

- Charms

- Cinderella

- Land music

- Cowboy poetry

- Creation stories

- Curses

- English language similes

- Epic poetry

- Legend

- Fairy tale

- Folk conventionalities

- Folk etymologies

- Folk metaphors

- Folk poetry

- Folk music

- Folksongs

- Folk spoken language

- Folktales of oral tradition

- Ghostlore

- Greetings

- Pig-calling

- Insults

- Jokes

- Keening

- Latrinalia

- Legends

- Limericks

- Lullabies

- Myth

- Oaths

- Leave-taking formulas

- Fakelore

- Place names

- Prayers at bedtime

- Proverbs

- Retorts

- Riddle

- Roasts

- Sagas

- Sea shanties

- Street vendors

- Superstition

- Tall tale

- Taunts

- Toasts

- Tongue-twisters

- Urban legends

- Word games

- Yodeling

Material culture [edit]

Equus caballus and sulky weathervane, Smithsonian American Art Museum

The genre of material culture includes all artifacts that can be touched, held, lived in, or eaten. They are tangible objects with a physical presence, either intended for permanent use or to be used at the next meal. Well-nigh of these folklore artifacts are single objects that have been created by manus for a specific purpose; withal, folk artifacts can too be mass-produced, such every bit dreidels or Christmas decorations. These items go along to exist considered folklore considering of their long (pre-industrial) history and their customary use. All of these cloth objects "existed prior to and proceed aslope mechanized industry. … [They are] transmitted beyond the generations and discipline to the same forces of conservative tradition and individual variation"[25] that are found in all folk artifacts. Folklorists are interested in the physical course, the method of industry or construction, the design of utilise, too every bit the procurement of the raw materials.[28] The pregnant to those who both make and use these objects is important. Of primary significance in these studies is the complex balance of continuity over modify in both their design and their decoration.

Traditional highlanders' pins hand-fabricated by a goldsmith in Podhale, Poland

In Europe, prior to the Industrial Revolution, everything was made by hand. While some folklorists of the 19th century wanted to secure the oral traditions of the rural folk earlier the populace became literate, other folklorists sought to identify mitt-crafted objects before their production processes were lost to industrial manufacturing. Just equally exact lore continues to be actively created and transmitted in today's culture, and then these handicrafts can still be found all effectually us, with perchance a shift in purpose and meaning. There are many reasons for standing to handmake objects for utilise, for example these skills may be needed to repair manufactured items, or a unique design might be required which is not (or cannot exist) plant in the stores. Many crafts are considered as simple home maintenance, such as cooking, sewing and carpentry. For many people, handicrafts have also become an enjoyable and satisfying hobby. Handmade objects are often regarded as prestigious, where extra time and thought is spent in their creation and their uniqueness is valued.[29] For the folklorist, these manus-crafted objects embody multifaceted relationships in the lives of the craftsmen and the users, a concept that has been lost with mass-produced items that take no connection to an private craftsman.[30]

Many traditional crafts, such every bit ironworking and glass-making, take been elevated to the fine or practical arts and taught in fine art schools;[31] or they take been repurposed as folk art, characterized as objects whose decorative form supersedes their utilitarian needs. Folk fine art is found in hex signs on Pennsylvania Dutch barns, tin man sculptures made by metalworkers, forepart yard Christmas displays, decorated school lockers, carved gun stocks, and tattoos. "Words such as naive, self-taught, and individualistic are used to describe these objects, and the exceptional rather than the representative cosmos is featured."[32] This is in contrast to the understanding of folklore artifacts that are nurtured and passed along within a customs.[note 4]

Many objects of material sociology are challenging to classify, difficult to annal, and unwieldy to store. The assigned job of museums is to preserve and brand use of these bulky artifacts of textile culture. To this cease, the concept of the living museum has adult, starting time in Scandinavia at the terminate of the 19th century. These open-air museums not merely brandish the artifacts, merely also teach visitors how the items were used, with actors reenacting the everyday lives of people from all segments of society, relying heavily on the cloth artifacts of a pre-industrial society. Many locations even duplicate the processing of the objects, thus creating new objects of an earlier historic time menstruum. Living museums are now institute throughout the world as office of a thriving heritage manufacture.

This listing represents merely a small sampling of objects and skills that are included in studies of material culture.

- Autograph books

- Bunad

- Embroidery

- Folk art

- Folk costume

- Folk medicines

- Nutrient recipes and presentation

- Foodways

- Common handicrafts

- Handmade toys

- Haystacks

- Hex signs

- Decorative ironworks

- Pottery

- Quilting

- Rock sculpting

- Tipis

- Traditional fences

- Vernacular architecture

- Weather vanes

- Woodworking

Community [edit]

Customary culture is remembered enactment, i.e. re-enactment. It is the patterns of expected beliefs within a group, the "traditional and expected way of doing things"[33] [34] A custom can be a single gesture, such as thumbs down or a handshake. It can also exist a complex interaction of multiple folk customs and artifacts as seen in a child'southward altogether political party, including exact lore (Happy Birthday song), fabric lore (presents and a birthday cake), special games (Musical chairs) and individual customs (making a wish as you lot blow out the candles). Each of these is a folklore antiquity in its own right, potentially worthy of investigation and cultural analysis. Together they combine to build the custom of a birthday political party commemoration, a scripted combination of multiple artifacts which have meaning within their social grouping.

Santa Claus giving gifts to children, a common folk practice associated with Christmas in Western nations

Hajji Firuz is a fictional character in Iranian folklore who appears in the streets by the start of Nowruz, dances through the streets while singing and playing tambourine.

Folklorists divide customs into several different categories.[33] A custom can exist a seasonal celebration, such as Thanksgiving or New Year's. It tin can be a life cycle celebration for an private, such every bit baptism, birthday or wedding. A custom can also marking a community festival or effect; examples of this are Carnival in Cologne or Mardi Gras in New Orleans. This category also includes the Smithsonian Folklife Festival celebrated each summer on the Mall in Washington, DC. A fourth category includes community related to folk beliefs. Walking under a ladder is just one of many symbols considered unlucky. Occupational groups tend to have a rich history of community related to their life and piece of work, and then the traditions of sailors or lumberjacks.[note 5] The surface area of ecclesiastical folklore, which includes modes of worship not sanctioned by the established church[35] tends to be so large and complex that it is usually treated as a specialized area of folk customs; information technology requires considerable expertise in standard church ritual in order to adequately translate folk customs and behavior that originated in official church practice.

Customary sociology is always a performance, be it a single gesture or a complex of scripted community, and participating in the custom, either as performer or audition, signifies acquittance of that social grouping. Some customary behavior is intended to exist performed and understood only inside the group itself, so the handkerchief code sometimes used in the gay customs or the initiation rituals of the Freemasons. Other community are designed specifically to stand for a social group to outsiders, those who do non belong to this grouping. The St. Patrick'due south Solar day Parade in New York and in other communities across the continent is a unmarried case of an ethnic grouping parading their separateness (differential behavior[36]), and encouraging Americans of all stripes to testify alliance to this colorful ethnic group.

Practitioners of hoodening, a folk custom found in Kent, southeastern England, in 1909

These festivals and parades, with a target audience of people who do not belong to the social group, intersect with the interests and mission of public folklorists, who are engaged in the documentation, preservation, and presentation of traditional forms of folklife. With a bully in popular involvement in folk traditions, these community celebrations are becoming more than numerous throughout the western world. While ostensibly parading the variety of their community, economic groups have discovered that these folk parades and festivals are practiced for business. All shades of people are out on the streets, eating, drinking and spending. This attracts support non only from the business community, but also from federal and land organizations for these local street parties.[37] Paradoxically, in parading diversity within the community, these events accept come to cosign truthful community, where business interests marry with the varied (folk) social groups to promote the interests of the community as a whole.

This is just a small sampling of types and examples of customary lore.

- Amish

- Barn raising

- Altogether

- Cakewalk

- Cat'due south cradle

- Chaharshanbe Suri

- Christmas

- Crossed fingers

- Folk dance

- Folk drama

- Folk medicine

- Giving the finger

- Halloween

- Hoodening

- Gestures

- Groundhog Day

- Louisiana Creole people

- Mime

- Native Hawaiians

- Ouiji board

- Powwows

- Practical jokes

- Saint John's Eve

- Shakers

- Symbols

- Thanksgiving

- Thumbs down

- Play tricks or Treating

- Whaling

- Yo-yos

Childlore and games [edit]

Childlore is a distinct branch of folklore that deals with activities passed on by children to other children, away from the influence or supervision of an adult.[38] Children'due south sociology contains artifacts from all the standard folklore genres of verbal, material, and customary lore; it is nevertheless the child-to-child conduit that distinguishes these artifacts. For babyhood is a social group where children teach, learn and share their ain traditions, flourishing in a street culture outside the purview of adults. This is likewise ideal where it needs to be nerveless; as Iona and Peter Opie demonstrated in their pioneering volume Children's Games in Street and Playground.[21] Here the social group of children is studied on its ain terms, not every bit a derivative of adult social groups. It is shown that the culture of children is quite distinctive; it is mostly unnoticed past the sophisticated world of adults, and quite as little afflicted by it.[39]

Of particular interest to folklorists hither is the mode of transmission of these artifacts; this lore circulates exclusively within an breezy pre-literate children'due south network or folk grouping. Information technology does not include artifacts taught to children by adults. However children tin can take the taught and teach it further to other children, turning it into childlore. Or they can take the artifacts and plough them into something else; so Old McDonald'south farm is transformed from beast noises to the scatological version of animate being poop. This childlore is characterized past "its lack of dependence on literary and fixed form. Children…operate among themselves in a earth of informal and voice communication, unimpeded by the necessity of maintaining and transmitting information by written means.[forty] This is as close as folklorists can come to observing the transmission and social function of this folk knowledge before the spread of literacy during the 19th century.

As nosotros have seen with the other genres, the original collections of children'due south lore and games in the 19th century was driven by a fear that the civilization of childhood would die out.[41] Early folklorists, among them Alice Gomme in Britain and William Wells Newell in the U.s., felt a need to capture the unstructured and unsupervised street life and activities of children before it was lost. This fright proved to be unfounded. In a comparison of any modern school playground during recess and the painting of "Children'south Games" by Pieter Breugel the Elder we tin can see that the activity level is similar, and many of the games from the 1560 painting are recognizable and comparable to modern variations all the same played today.

These same artifacts of childlore, in innumerable variations, also continue to serve the same office of learning and practicing skills needed for growth. So bouncing and swinging rhythms and rhymes encourage development of balance and coordination in infants and children. Verbal rhymes similar Peter Piper picked... serve to increase both the oral and aural vigil of children. Songs and chants, accessing a different part of the encephalon, are used to memorize serial (Alphabet song). They too provide the necessary beat to complex concrete rhythms and movements, be it hand-clapping, jump roping, or ball bouncing. Furthermore, many physical games are used to develop strength, coordination and endurance of the players. For some squad games, negotiations virtually the rules can run on longer than the game itself every bit social skills are apposite.[42] Even as we are just now uncovering the neuroscience that undergirds the developmental function of this childlore, the artifacts themselves have been in play for centuries.

Below is listed only a minor sampling of types and examples of childlore and games.

- Cadet buck

- Counting rhymes

- Dandling rhymes

- Finger and toe rhymes

- Counting-out games

- Dreidel

- Eeny, meeny, miny, moe

- Games

- Traditional games

- London Bridge Is Falling Down

- Lullabies

- Plant nursery rhymes

- Playground songs

- Ball-bouncing rhymes

- Rhymes

- Riddles

- Ring a Band o Roses

- Spring-rope rhymes

- Stickball

- Street games

Folk history [edit]

A case has been made for because folk history every bit a singled-out sub-category of folklore, an idea that has received attention from such folklorists as Richard Dorson. This field of study is represented in The Sociology Historian, an annual journal sponsored by the History and Folklore Section of the American Sociology Social club and concerned with the connections of folklore with history, every bit well as the history of folklore studies.[43]

The study of folk history is particularly well developed in Ireland, where the Handbook of Irish Folklore (the standard book used by field workers of the Irish gaelic Folklore Commission) recognizes "historical tradition" equally a divide category, traditionally referred to equally seanchas.[44] Henry Glassie made a pioneering contribution in his classic study, Passing the Fourth dimension in Ballymenone.[45] Another notable exponent is historian Guy Beiner who has presented in-depth studies of Irish folk history, identifying a number of characteristic genres for what he has named "history telling", such as stories (divided into tales and "mini-histories"), songs and ballads (especially insubordinate songs), poems, rhymes, toasts, prophecies, proverbs and sayings, place-names, and a diverseness of commemorative ritual practices. These are frequently recited by dedicated storytellers (seanchaithe) and folk historians (staireolaithe).[46] Beiner has since adopted the term vernacular historiography in an try to motion beyond the confines of "the artificial divides between oral and literary cultures that prevarication at the heart of conceptualizations of oral tradition".[47]

Folklore performance in context [edit]

Folk-dance-kalash in Islamic republic of pakistan

Defective context, folklore artifacts would be uninspiring objects without any life of their own. It is merely through performance that the artifacts come alive every bit an active and meaningful component of a social group; the intergroup advice arises in the performance and this is where transmission of these cultural elements takes place. American folklorist Roger D. Abrahams has described it thus: "Folklore is folklore only when performed. As organized entities of performance, items of folklore have a sense of command inherent in them, a power that can be capitalized upon and enhanced through effective operation."[48] Without transmission, these items are not folklore, they are only individual quirky tales and objects.

This understanding in folkloristics only occurred in the second half of the 20th century, when the two terms "folklore performance" and "text and context" dominated discussions among folklorists. These terms are not contradictory or even mutually sectional. Equally borrowings from other fields of study, one or the other linguistic formulation is more appropriate to any given give-and-take. Performance is ofttimes tied to verbal and customary lore, whereas context is used in discussions of textile lore. Both formulations offer unlike perspectives on the aforementioned folkloric agreement, specifically that sociology artifacts need to remain embedded in their cultural environment if we are to gain insight into their meaning for the community.

The concept of cultural (sociology) performance is shared with ethnography and anthropology among other social sciences. The cultural anthropologist Victor Turner identified 4 universal characteristics of cultural functioning: playfulness, framing, the use of symbolic language, and employing the subjunctive mood.[49] In viewing the performance, the audience leaves the daily reality to move into a manner of make-believe, or "what if?" It is self-evident that this fits well with all types of verbal lore, where reality has no place amid the symbols, fantasies, and nonsense of traditional tales, proverbs, and jokes. Customs and the lore of children and games also fit easily into the linguistic communication of a folklore performance.

Material civilisation requires some moulding to turn it into a performance. Should we consider the performance of the creation of the artifact, as in a quilting party, or the performance of the recipients who use the quilt to cover their marriage bed? Here the language of context works improve to describe the quilting of patterns copied from the grandmother, quilting as a social outcome during the wintertime months, or the gifting of a quilt to signify the importance of the event. Each of these—the traditional design chosen, the social consequence, and the gifting—occur within the broader context of the customs. Notwithstanding, when because context, the structure and characteristics of performance tin exist recognized, including an audience, a framing issue, and the apply of decorative figures and symbols, all of which go beyond the utility of the object.

Backstory [edit]

Before the Second World War, folk artifacts had been understood and collected as cultural shards of an before fourth dimension. They were considered individual vestigial artifacts, with petty or no function in the contemporary culture. Given this understanding, the goal of the folklorist was to capture and document them before they disappeared. They were collected with no supporting data, bound in books, archived and classified more or less successfully. The Historic–Geographic Method worked to isolate and rail these collected artifacts, mostly verbal lore, beyond space and fourth dimension.

Following the 2d Globe War, folklorists began to articulate a more holistic approach toward their field of study matter. In tandem with the growing sophistication in the social sciences, attending was no longer limited to the isolated artifact, but extended to include the artifact embedded in an active cultural environs. One early proponent was Alan Dundes with his essay "Texture, Text and Context", starting time published 1964.[l] A public presentation in 1967 by Dan Ben-Amos at the American Folklore Society brought the behavioral approach into open debate amidst folklorists. In 1972 Richard Dorson called out the "young Turks" for their motion toward a behavioral approach to folklore. This arroyo "shifted the conceptualization of folklore equally an extractable item or 'text' to an emphasis on folklore as a kind of homo behavior and advice. Conceptualizing folklore as behavior redefined the chore of folklorists..."[51] [notation 6]

Folklore became a verb, an action, something that people do, not just something that they have.[52] It is in the performance and the agile context that folklore artifacts become transmitted in informal, direct communication, either verbally or in sit-in. Performance includes all the different modes and manners in which this transmission occurs.

Tradition-bearer and audience [edit]

Manual is a communicative process requiring a binary: one individual or group who actively transmits data in some class to some other individual or group. Each of these is a defined part in the folklore process. The tradition-bearer[53] is the individual who actively passes forth the knowledge of an artifact; this can exist either a mother singing a lullaby to her baby, or an Irish dance troupe performing at a local festival. They are named individuals, usually well known in the customs every bit knowledgeable in their traditional lore. They are non the bearding "folk", the nameless mass without of history or individuality.

The audience of this functioning is the other half in the transmission process; they listen, watch, and remember. Few of them will become active tradition-bearers; many more will be passive tradition-bearers who maintain a memory of this specific traditional artifact, in both its presentation and its content.

In that location is active communication between the audience and the performer. The performer is presenting to the audience; the audition in plough, through its deportment and reactions, is actively communicating with the performer.[54] The purpose of this operation is not to create something new merely to re-create something that already exists; the performance is words and deportment which are known, recognized and valued past both the performer and the audience. For folklore is kickoff and foremost remembered behavior. Every bit members of the aforementioned cultural reference group, they place and value this performance as a piece of shared cultural cognition.

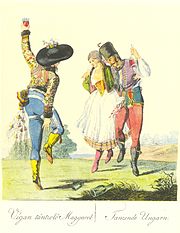

Dancing Hungarians by J. B. Heinbucher, 1816

Some elements of folk culture might be in the center of local culture and an import part of cocky-identity. For instance folk dance is highly popular in Estonia and it has evolved into a sort of a national sport.[notation 7] Nineteen Estonian Dance Celebration in 2015 that was held together with Estonian Song Festival.

Framing the performance [edit]

To initiate the performance, there must be a frame of some sort to point that what is to follow is indeed performance. The frame brackets it as exterior of normal discourse. In customary lore such every bit life bicycle celebrations (ex. birthday) or trip the light fantastic toe performances, the framing occurs as office of the event, ofttimes marked by location. The audience goes to the event location to participate. Games are defined primarily by rules,[55] it is with the initiation of the rules that the game is framed. The folklorist Barre Toelken describes an evening spent in a Navaho family unit playing string figure games, with each of the members shifting from performer to audience every bit they create and brandish dissimilar figures to each other.[56]

In exact lore, the performer volition start and end with recognized linguistic formulas. An easy instance is seen in the common introduction to a joke: "Have you heard the i...", "Joke of the day...", or "An elephant walks into a bar". Each of these signals to the listeners that the following is a joke, not to be taken literally. The joke is completed with the punch line of the joke. Another traditional narrative marker in English is the framing of a fairy tale betwixt the phrases "Once upon a time" and "They all lived happily ever later on." Many languages accept similar phrases which are used to frame a traditional tale. Each of these linguistic formulas removes the bracketed text from ordinary discourse, and marks it as a recognized form of stylized, formulaic communication for both the performer and the audition.

In the subjunctive voice [edit]

Framing as a narrative device serves to signal to both the story teller and the audience that the narrative which follows is indeed a fiction (verbal lore), and not to exist understood equally historical fact or reality. It moves the framed narration into the subjunctive mood, and marks a space in which "fiction, history, story, tradition, art, teaching, all be within the narrated or performed expressive 'event' outside the normal realms and constraints of reality or time."[57] This shift from the realis to the irrealis mood is understood past all participants inside the reference grouping. It enables these fictional events to comprise pregnant for the group, and tin can lead to very real consequences.[58]

Anderson's law of machine-correction [edit]

The theory of self-correction in folklore transmission was first articulated by the folklorist Walter Anderson in the 1920s; this posits a feedback mechanism which would keep sociology variants closer to the original form.[59] [note eight] This theory addresses the question about how, with multiple performers and multiple audiences, the artifact maintains its identity across time and geography. Anderson credited the audience with censoring narrators who deviated also far from the known (traditional) text.[lx]

Any performance is a two-way advice process. The performer addresses the audition with words and actions; the audience in turn actively responds to the performer. If this performance deviates besides far from audience expectations of the familiar folk artifact, they will answer with negative feedback. Wanting to avoid more negative reaction, the performer will adapt his performance to adapt to audition expectations. "Social reward by an audition [is] a major factor in motivating narrators..."[61] It is this dynamic feedback loop betwixt performer and audition which gives stability to the text of the performance.[62]

In reality, this model is not then simplistic; there are multiple redundancies in the agile folklore process. The performer has heard the tale multiple times, he has heard it from different story tellers in multiple versions. In turn, he tells the tale multiple times to the same or a different audience, and they wait to hear the version they know. This expanded model of redundancy in a non-linear narrative process makes it hard to innovate during any unmarried performance; corrective feedback from the audience will exist immediate.[63] "At the middle of both autopoetic self-maintenance and the 'virality' of meme manual... it is enough to assume that some sort of recursive activeness maintains a degree of integrity [of the artifact] in certain features ... sufficient to allow u.s. to recognize it equally an instance of its blazon."[64]

Context of material lore [edit]

For textile folk artifacts, it becomes more fruitful to return to the terminology of Alan Dundes: text and context. Here the text designates the physical antiquity itself, the single item fabricated by an individual for a specific purpose. The context is and so unmasked by observation and questions concerning both its product and its usage. Why was it made, how was it made, who will use it, how volition they utilise it, where did the raw materials come from, who designed it, etc. These questions are limited only by the skill of the interviewer.

In his study of southeastern Kentucky chair makers, Michael Owen Jones describes production of a chair inside the context of the life of the craftsman.[65] For Henry Glassie in his study of Folk Housing in Centre Virginia, the investigation concerns the historical pattern he finds repeated in the dwellings of this region: the house is planted in the landscape but as the mural completes itself with the house.[66] The artisan in his roadside stand or store in the nearby town wants to make and display products which appeal to customers. There is "a craftsperson'due south eagerness to produce 'satisfactory items' due to a close personal contact with the customer and expectations to serve the customer again." Here the role of consumer "... is the basic force responsible for the continuity and aperture of behavior."[61]

In cloth culture the context becomes the cultural environment in which the object is made (chair), used (house), and sold (wares). None of these artisans is "bearding" folk; they are individuals making a living with the tools and skills learned within and valued in the context of their community.

Toelken'due south conservative-dynamic continuum [edit]

No two performances are identical. The performer attempts to continue the performance within expectations, but this happens despite a multitude of changing variables. He has given this performance one time more or less, the audition is different, the social and political environs has changed. In the context of material culture, no 2 hand-crafted items are identical. Sometimes these deviations in the functioning and the product are unintentional, just part of the process. Just sometimes these deviations are intentional; the performer or artisan desire to play with the boundaries of expectation and add their own creative impact. They perform within the tension of conserving the recognized class and adding innovation.

The folklorist Barre Toelken identifies this tension as "a combination of both irresolute ('dynamic') and static ('conservative') elements that evolve and change through sharing, communication and performance."[67] Over fourth dimension, the cultural context shifts and morphs: new leaders, new technologies, new values, new sensation. As the context changes, and so must the artifact, for without modifications to map existing artifacts into the evolving cultural mural, they lose their meaning. Joking equally an active class of verbal lore makes this tension visible as joke cycles come and go to reflect new bug of business concern. One time an artifact is no longer applicable to the context, transmission becomes a nonstarter; information technology loses relevancy for a contemporary audience. If it is not transmitted, then it is no longer folklore and becomes instead an historic relic.[61]

In the electronic age [edit]

Folklorists take begun to identify how the advent of electronic communications will modify and change the performance and manual of folklore artifacts. It is clear that the internet is modifying folkloric process, non killing it, equally despite the historic association between folklore and anti-modernity, people keep to apply traditional expressive forms in new media, including the internet.[68] Jokes and joking are equally plentiful as e'er both in traditional face-to-face interactions and through electronic manual. New communication modes are besides transforming traditional stories into many unlike configurations. The fairy tale Snow White is now offered in multiple media forms for both children and adults, including a television show and video game.[ citation needed ]

See also [edit]

- Applied folklore

- Costumbrismo

- Family folklore

- Folkloristics

- Folklore studies

- Intangible cultural heritage

- Legend

- Memetics

- Public folklore

- The law of conservation of misery

Notes [edit]

- ^ The word folkloristics is favored past Alan Dundes, and used in the championship of his publication Dundes 1978; the term folklore studies is defined and used by Simon Bronner, see Bronner 1986, p. xi.

- ^ Contributors of this issue were, among others, Claire Farrer, Joan N. Radner, Susan Lanser, Elaine Lawless, and Jeannie B. Thomas.

- ^ Vladimir Propp get-go defined a uniform structure in Russian fairy tales in his groundbreaking monograph Morphology of the Folktale, published in Russian in 1928. Encounter Propp 1928

- ^ Henry Glassie, a distinguished folklorist studying applied science in cultural context, notes that in Turkish ane discussion, sanat, refers to all objects, not distinguishing betwixt art and craft. The latter stardom, Glassie emphasizes, is non based on medium just on social class. This raises the question every bit to the difference betwixt craft; is the divergence found only in the labeling?

- ^ The folklorist Archie Green specialized in workers' traditions and the lore of labor groups.

- ^ A more extensive discussion of this tin can be found in "The 'Text/Context' Controversy and the Emergence of Behavioral Approaches in Sociology", Gabbert 1999

- ^ See Folk dance Estonica

- ^ Anderson is best known for his monograph Kaiser und Abt (Folklore Fellows' Communications 42, Helsinki 1923) on folktales of blazon AT 922.

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ A legend is a traditional story sometimes popularly regarded every bit historical merely unauthenticated.

- ^ "Sociology Programs in the US and Canada". cfs.osu.edu. Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 8 Nov 2018. Retrieved 21 Baronial 2020.

- ^ "William John Thoms". The Folklore Society. Archived from the original on fifteen July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ "lore – Definition of lore in English". Oxford Dictionaries . Retrieved eight October 2017.

- ^ Dundes 1969, p. xiii, footnote 34

- ^ Wilson 2006, p. 85

- ^ a b Dundes 1980, p. 7

- ^ a b Bauman 1971

- ^ Dundes 1971

- ^ Dundes 1965, p. one

- ^ Schreiter 2015, p.[ page needed ].

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, pp. 7–eight

- ^ Noyes 2012, p. xx

- ^ Noyes 2012, pp. 15–16

- ^ Zumwalt & Dundes 1988

- ^ "Public Constabulary 94-201: The Creation of the American Folklife Center". loc.gov/folklife. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Hufford 1991

- ^ Bascom 1954.

- ^ Dundes 1980, p. 8

- ^ Bauman 1971, p. 41

- ^ a b Opie & Opie 1969

- ^ Georges & Jones 1995, pp. 10–12

- ^ Toelken 1996, p. 184

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, p. 17

- ^ a b Dorson 1972, p. 2

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, p. 13

- ^ Georges & Jones 1995, pp. 112–113

- ^ Vlach 1997

- ^ Roberts 1972, pp. 236 ff

- ^ Schiffer 2000.

- ^ Roberts 1972, pp. 236 ff, 250

- ^ "Material Culture". American Folklife Center. The Library of Congress. 29 October 2010. Archived from the original on xx Baronial 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ a b Sweterlitsch 1997, p. 168

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, p. 16

- ^ Dorson 1972, p. four

- ^ Bauman 1971, p. 45

- ^ Sweterlitsch 1997, p. 170

- ^ Grider 1997, p. 123

- ^ Grider 1997, p. 125

- ^ Grider 1997

- ^ Grider 1997, p. 127

- ^ Georges & Jones 1995, p. 243–254

- ^ "The Folklore Historian". American Sociology Social club.

- ^ Ó Súilleabháin 1942, p. 520–547.

- ^ Glassie 1982a.

- ^ Beiner 2007, p. 81–123

- ^ Beiner 2018, p. 13–14

- ^ Abrahams 1972, p. 35

- ^ Ben-Amos 1997a, pp. 633–634

- ^ Dundes 1980

- ^ Gabbert 1999, p. 119

- ^ Bauman & Paredes 1972, p. xv

- ^ Ben-Amos 1997b

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, p. 127

- ^ Beresin 1997, p. 393

- ^ Toelken 1996, pp. 118 ff

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, p. 141

- ^ Ben-Amos 1997a

- ^ Dorst 2016, p. 131

- ^ El-Shamy 1997

- ^ a b c El-Shamy 1997, p. 71

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, p. 127

- ^ Dorst 2016, pp. 131–132

- ^ Dorst 2016, p. 138

- ^ Jones 1975, p.[ page needed ].

- ^ Glassie 1983, p. 125.

- ^ Sims & Stephens 2005, p. 10

- ^ Blank & Howard 2013, p. 4, nine, 11

References [edit]

- Anderson, Walter (1923). "Kaiser und Abt. Die Geschichte eines Schwanks". FF Communications. 42.

- Bascom, William R. (1954). "Iv Functions of Folklore". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 67 (266): 333–349. doi:10.2307/536411. JSTOR 536411.

- Bauman, Richard (1971). "Differential Identity and the Social Base of operations of Folklore". Journal of American Folklore. 84 (331): 31–41. doi:ten.2307/539731. JSTOR 539731.

- Bauman, Richard; Paredes, Américo, eds. (1972). Toward New Perspectives in Sociology. Bloomington, IN: Trickster Press.

- Abrahams, Roger D. (1972). "Personal Ability and Social Restraint". In Bauman, Richard; Paredes, Américo (eds.). Toward New Perspectives in Folklore. Bloomington, IN: Trickster Printing. pp. 20–39.

- Ben-Amos, Dan (1972). "Toward a Definition of Sociology in Context". In Bauman, Richard; Paredes, Américo (eds.). Toward New Perspectives in Sociology. Bloomington, IN: Trickster Press. pp. 3–xv.

- Bauman, Richard (1975). "Exact Art as Performance". American Anthropologist. New Serial. 77 (2): 290–311. doi:10.1525/aa.1975.77.2.02a00030. JSTOR 674535.

- Bauman, Richard (2008). "The Philology of the Vernacular". Journal of Folklore Inquiry. 45 (ane): 29–36. doi:10.2979/JFR.2008.45.1.29. JSTOR 40206961. S2CID 144402948.

- Beiner, Guy (2007). Remembering the Year of the French: Irish Folk History and Social Memory. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN978-0-299-21824-9.

- Beiner, Guy (2018). Forgetful Remembrance: Social Forgetting and Vernacular Historiography of a Rebellion in Ulster. Oxford: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-nineteen-874935-vi.

- Ben-Amos, Dan (1985). "On the Last [due south] in 'Folkloristics'". Journal of American Folklore. 98 (389): 334–336. doi:ten.2307/539940. JSTOR 539940.

- Bendix, Regina (1997). In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN978-0-299-15544-5.

- Bendix, Regina; Hasan-Rokem, Galit, eds. (2012). A Companion to Folklore. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN978-i-4051-9499-0.

- Noyes, Dorothy (2012). "The Social Base of operations of Sociology". In Bendix, Regina; Hasan-Rokem, Galit (eds.). A Companion to Folklore. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 13–39.

- Blank, Trevor J., ed. (2009). Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital Globe. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press. ISBN978-0-87421-750-half dozen.

- Frank, Russel (2009). "The Forrard as Folklore: Studying E-Mailed Humor". In Bare, Trevor J. (ed.). Folklore and the Internet: Colloquial Expression in a Digital Earth. Logan, UT: Utah Country University Press. pp. 98–122.

- Blank, Trevor J.; Howard, Robert Glenn, eds. (2013). Tradition in the 21st Century: Locating the Role of the Past in the Present. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press.

- Bronner, Simon J. (1986). American Folklore Studies: An Intellectual History. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN978-0-7006-0313-eight.

- Bronner, Simon J. (1998). Following Tradition: Folklore in the Discourse of American Civilization. Logan, UT: Utah State Academy Press. ISBN978-0-87421-239-half-dozen.

- Bronner, Simon J. (2017). Folklore: The Basics. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN978-1-138-77495-vii.

- Bronner, Simon J., ed. (2007). The Meaning of folklore: the Analytical Essays of Alan Dundes. Logan, UT: Utah Country University Printing. ISBN978-0-87421-683-7.

- Brunvand, Jan Harold (1968). The Written report of American Folklore . New York; London: W.W. Norton. ISBN978-0-39309957-7.

- Burns, Thomas A. (1977). "Folkloristics: A Formulation of Theory". Western Folklore. 36 (two): 109–34. doi:10.2307/1498964. JSTOR 1498964.

- Del-Rio-Roberts, Maribel (2010). "A Guide to Conducting Ethnographic Enquiry: A Review of Ethnography: Step-by-Step (3rd ed.) by David M. Fetterman" (PDF). The Qualitative Written report. fifteen (iii): 737–49.

- Deloria, Vine (1994). God Is Carmine: A Native View of Organized religion. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing. ISBN978-1-55591-176-viii.

- Dorson, Richard M., ed. (1972). Folklore and Folklife: an Introduction . Chicago: University of Chicago Printing. ISBN9780226158709.

- Roberts, Warren (1972). "Folk Crafts". In Dorson, Richard M. (ed.). Folklore and Folklife: an Introduction. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press. pp. 233–252. ISBN9780226158709.

- Dorson, Richard 1000. (1976). Folklore and Fakelore: Essays Toward a Discipline of Folk Studies. Cambridge; London: Harvard Academy Press. ISBN978-0-674-33020-7.

- Dorst, John (1990). "Tags and Burners, Cycles and Networks: Folklore in the Telectronic Historic period". Journal of Folklore Research. 27 (3): 61–108.

- Dorst, John (2016). "Folklore'south Cybernetic Imaginary, or, Unpacking the Obvious". Journal of American Folklore. 129 (512): 127–145. doi:x.5406/jamerfolk.129.512.0127. JSTOR 10.5406/jamerfolk.129.512.0127. S2CID 148523716.

- Dundes, Alan (1965). The Study of Folklore . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN978-0-13-858944-8.

- Dundes, Alan (1969). "The Devolutionary Premise in Folklore Theory". Journal of the Folklore Found. half dozen (1): 5–19. doi:10.2307/3814118. JSTOR 3814118.

- Dundes, Alan (1971). "Folk Ideas as Units of Worldview". Journal of American Sociology. 84 (331): 93–103. doi:ten.2307/539737. JSTOR 539737.

- Dundes, Alan (1978). Essays in Folkloristics (Kirpa Dai series in sociology and anthropology). Sociology Constitute.

- Dundes, Alan (1978a). "Into the Endzone for a Touchdown: A Psychoanalytic Consideration of American Football". Western Sociology. 37 (2): 75–88. doi:10.2307/1499315. JSTOR 1499315.

- Dundes, Alan (1980). Interpreting Sociology. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana Academy Press. ISBN978-0-253-14307-v.

- Dundes, Alan (1984). Life Is like a Chicken Coop Ladder. A Portrait of German Culture through Folklore . New York: Columbia Academy Press. ISBN978-0-231-05494-2.

- Dundes, Alan (2005). "Folkloristics in the Twenty-Starting time Century (AFS Invited Presidential Plenary Address, 2004)". Journal of American Folklore. 118 (470): 385–408. doi:10.1353/jaf.2005.0044. JSTOR 4137664. S2CID 161269637.

- Ellis, Nib (2002). "Making a Big Apple Crumble". New Directions in Folklore (half dozen). Archived from the original on 2016-x-22. Retrieved 2016-12-19 .

- Fixico, Donald L. (2003). The American Indian Listen in a Linear Earth. New York: Routledge. ISBN978-0-415-94456-4.

- Gabbert, Lisa (1999). "The "Text/Context" Controversy and the Emergence of Behavioral Approaches in Folklore" (PDF). Folklore Forum. 30 (112): 119–128.

- Gazin-Schwartz, Amy (2011). "Myth and Folklore". In Insoll, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Faith. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 63–75. ISBN978-0-19-923244-4.

- Genzuk, Michael (2003). "A Synthesis of Ethnographic Research" (PDF). Occasional Papers Series. Heart for Multilingual, Multicultural Research. University of Southern California. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- Georges, Robert A.; Jones, Michael Owen (1995). Folkloristics : an Introduction. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN978-0-253-20994-eight.

- Glassie, Henry (1975). Folk Housing in Middle Virginia: A Structural Assay of Historic Artifacts. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Printing.

- Glassie, Henry (1982a). Passing the Time in Ballymenone: Civilization and History of an Ulster Community. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Glassie, Henry (1982b). Irish Folk History: Folktales from the North. Dublin: O'Brien Press.

- Glassie, Henry (1983). "The Moral Lore of Folklore" (PDF). Folklore Forum. 16 (2): 123–151.

- Goody, Jack (1977). The Domestication of the Savage Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-521-29242-nine.

- Light-green, Thomas A., ed. (1997). Folklore: An Encyclopedia of Behavior, Community, Tales, Music, and Fine art. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN978-0-87436-986-1.

- Beresin, Ann Richman. "Games". In Green (1997), pp. 393–400.

- Ben-Amos, Dan (1997a). "Performance". in Green (1997), pp. 630–635.

- Ben-Amos, Dan (1997b). "Tradition-Bearer". in Green (1997), pp. 802–803.

- El-Shamy, Hasan. "Audience". In Greenish (1997), pp. seventy–72.

- Grider, Sylvia. "Children'south Sociology". In Green (1997), pp. 123–128.

- Sweterlitsch, Richard. "Custom". In Green (1997), pp. 168–172.

- Vlach, John. "Fabric Culture". In Green (1997), pp. 540–544.

- Hufford, Mary (1991). "American Folklife: A Democracy of Cultures". Publication of the American Folklife Center. 17: one–23.

- Jones, Michael Owen (1975). The Hand Made Object and Its Maker . Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Printing. ISBN9780520026971.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara (1985). "Di folkloristik: A Good Yiddish Word". Periodical of American Folklore. 98 (389): 331–334. doi:10.2307/539939. JSTOR 539939.

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara (September 1999). "Performance Studies". Rockefeller Foundation, Culture and Creativity.

- Mason, Bruce Lionel (Oct 1998). "E-Texts: The Orality and Literacy Issue Revisited". Oral Tradition. Columbia, MO: Centre for Studies in Oral Tradition. 13 (2).

- Noyes, Dorothy (2003). "Group". In Feintuch, Burt (ed.). Viii Words for the Study of Expressive Civilization. Academy of Illinois Press. pp. 7–41. ISBN978-0-252-07109-6. JSTOR 10.5406/j.ctt2ttc8f.5.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1969). Children'due south Games in Street and Playground. Oxford University Press.

- Oring, Elliott (1986). Folk Groups and Folklore Genres: An Introduction. Logan, UT: Utah State University Printing. ISBN978-0-87421-128-iii.

- Ó Súilleabháin, Seán (1942). A Handbook of Irish gaelic Sociology. Dublin: The Education Company of Republic of ireland Ltd.

- Propp, Vladimir (1928). Morphology of the Folktale. Saint petersburg.

- Raskin, Victor, ed. (2008). Primer of Humor Research: Humor Research 8. Berlin; New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Schiffer, Michael B. (October 2000). "Material Civilization (review)". Engineering science and Culture. 41 (4): 791–793. doi:10.1353/tech.2000.0178. S2CID 109662410.

- Schmidt-Lauber, Brigitta (2012-03-22). "Seeing, Hearing, Feeling, Writing". In Bendix, Regina; Hasan-Rokem, Galit (eds.). A Companion to Sociology. Chichester, Great britain: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 559–578. doi:10.1002/9781118379936.ch29. ISBN978-ane-118-37993-half-dozen.

- Schreiter, Robert J. (2015). Amalgam Local Theologies (30th Anniversary ed.). Orbis Books. ISBN978-ane-62698-146-i. OCLC 1054909858.

- Sims, Martha; Stephens, Martine (2005). Living Sociology: Introduction to the Study of People and their Traditions. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press. ISBN978-0-87421-611-0.

- Šmidchens, Guntis (1999). "Folklorism Revisited". Journal of American Folklore Enquiry. 36 (1): 51–70. JSTOR 3814813.

- Stahl, Sandra Dolby (1989). Literary Folkloristics and the Personal Narrative . Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN978-0-253-33515-9.

- Toelken, Barre (1996). The Dynamics of Sociology. Logan, UT: Utah State Academy Press. ISBN978-0-87421-203-7.

- Wilson, William A. (2006). Rudy, Jill Terry; Call, Diane (eds.). The Marrow of Human Experience: Essays on Folklore. Logan, UT: Utah Country University Press. ISBN978-0-87421-653-0. JSTOR j.ctt4cgkmk.

- Wolf-Knuts, Ulrika (1999). "On the history of comparison in sociology studies". Folklore Fellows' Summer School.

- Zumwalt, Rosemary Levy; Dundes, Alan (1988). American Folklore Scholarship: A Dialogue of Dissent. Indiana University Press.

- "Legend" definition in folktale | Dictionary.com [1]

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Folklore at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Folklore at Wikimedia Commons

- ^ https://world wide web.dictionary.com/scan/legend

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folklore

0 Response to "Anthropologists Prefer to Use the Term Verbal Arts Rather Than the Term Folklore Because the Term"

Post a Comment